Introduction to Meghadūtam by Kālidāsa

A Message Carried by a Cloud: The Journey of Love: Episode 3

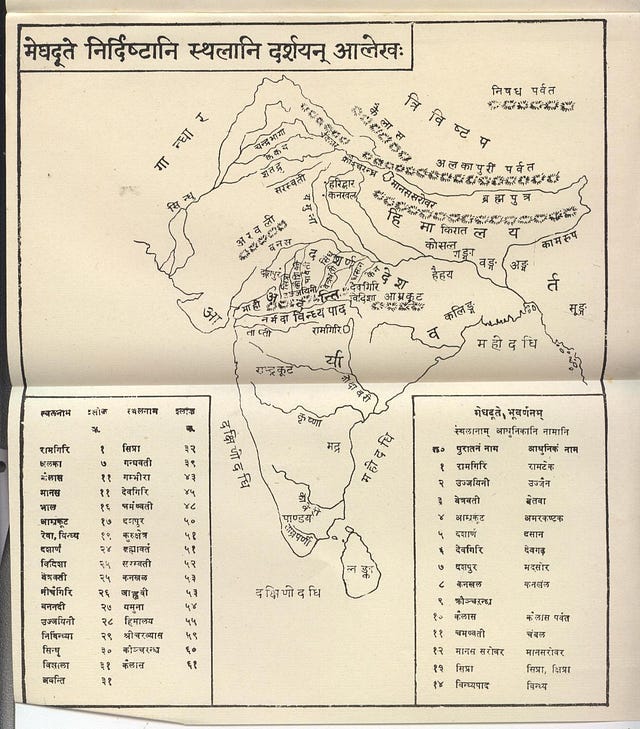

The Poetic Geography of the Cloud’s Journey

From Ramagiri (likely present-day Ramtek) to Alakapuri in the Himalayas, the cloud’s path follows a poetic yet realistic route through India. The journey covers key places:

Amrakoota (Amarkantak): The source of the Narmada River.

Dasharna (Chhattisgarh): Land of fragrant blooms.

Vidisha and Ujjaini: Famous cultural hubs.

Ranthambore and Kurukshetra: Moving towards the northern plains and spiritual centers.

Kalidasa appears to have travelled extensively in the northern Indian plains and possibly in the Himalayas. His descriptions of flora and fauna in these regions are proof not just of his journeys, but of his keen observation skills. His descriptions of geography show that he had a deep knowledge of the Indian terrain

In The Meghadootam, Yaksha gives Megha precise directions from Ramagiri (most likely present day Ramtek, near Nagpur) to Alkapuri. Of course, the poet does take some liberties after all a cloud moves directionless, sometimes buffeted by strong winds yet the basic contours of the journey are correct.

A possible reason for the meandering could be Kalidasa's desire to include his favourite places of pilgrimage in the poem. Therefore, he makes Megha arrive at Amrakoota hill, northeast of Ramagiri. Amrakoota is present day Amarkantak where the Satpura and the Vindhya ranges meet. It is the source of the holy river Narmada and of the river Sone. Situated 228 kilometres from Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh, it is a pilgrimage centre of immense importance.

Yaksha then asks Megha not to overstay his welcome at Amrakoota, but to move on over the Vindhya foothills, over a ragged terrain littered with stones (1.20). The next port of arrival is Dasharna country, most likely present-day Chhattisgarh south of Amrakoota, where flower-laden gardens are hedged by fragrant kewra blooms (1.25).

From here Megha moves to Vidisha, near the famous hamlet of Sanchi, a short journey from present day Bhopal (1.26). The poet now takes Megha straight to Ujjaini, his beloved city, situated west of Vidisha (1.29). The directions are accurate.

From Ujjaini Megha is asked to float northwest to Devagiri, most likely Devagadh, situated about one hundred kilometres southwest of Jhansi. Geographically the movement is towards the northern plains because the final destination is Alkapuri in the Himalayas.

Crossing the river Chambal (1.49), floating over Ranthambore, Megha arrives at Kurukshetra in present day Haryana, west of Delhi. He is directed to fly over to Haridwar and Kankhala northwards (1.54). Till now the journey is precise. Thereafter imagination takes over.

So this was India as Kalidasa knew her in all her expanse: holy places, verdant hills, sacred rivers, fertile tracts of land, magnificent capitals. An India where kings were consistently at war with each other, but occasionally came together to woo a charming princess. An India of rich and colourful cities.

Kālidāsa: The Poet of Hope, Romance, and Nature

Kālidāsa’s poetry reflects not only personal emotions but also the spirit of the times in which he lived. His works brim with joy, hope, romance, and moral values, painting a vibrant picture of an India rich in nature, spirituality, and human relationships.

The story of Kalidasa’s Yaksha pining for his beloved is a poignant, yet a sweet tale. Feel for him without feeling depressed. Of course, it’s just not possible to be depressed while reading Kalidasa. He was a poet of hope, of romance, of valour, of moral values, of courage and a master of writing about uplifting mythology and tendering ennobling practical advice.

Kalidasa lived and wrote in colourful times, and his works reflected those vibrant colours. In them we find joy, hope, moral values, romance, charity, kindness, a love of nature and high ideals. By any standard, those were great times in India’s history. Kalidasa has immortalised them in his words more successfully than any king or sculptor could do in rock edicts or in stone sculptures.

Conclusion

In Meghadūtam, Kālidāsa immortalizes universal themes of love, loss, and hope. The poem resonates with readers across time, capturing the essence of human experience with poetic finesse. As M.R. Kale remarked, “Man attains his dignity by recognizing that he is not independent of the natural world, but connected to it.”

Kālidāsa’s descriptions, drawn from his observations and extensive travels, offer insights into both human emotion and the physical world. Meghadūtam remains a timeless testament to the power of poetry to blend human and natural realms, making it a cornerstone of classical Indian literature.

We will explore this masterpiece further in future discussions, delving deeper into its themes, structure, and enduring relevance.

Bibliography:

Kālidāsa’s Meghadūtam

Kālidāsa. Meghadūtam. Translation and commentary by M.R. Kale.

Kalidasa: The Meghadootam A rendering in modern English, Translated by Rajendra Tandon

Sri Aurobindo’s commentary on Kālidāsa’s rhythm and phrasing.